Keep On Truckin’ 10.5.12

Artist Himmelfarb returns to Omaha via new ‘vehicle’ at MAM

by Janet L. Farber

Artists from outside Omaha have always had a presence in the local art scene. They help to keep the artistic landscape varied and lively, enhancing the conversation about how regional artists partake of a national or even international dialogue. Some of these “carpetbaggers” are shown but once, while others become returning favorites.

Among the latter, Chicago-based artist John Himmelfarb has been exhibiting his lively, retro-modernist flavored paintings, prints and drawings in Omaha for so long that he's no longer thought of as an outsider, but more like a visiting relative who never truly outstays his welcome. It is with anticipation that the nationally recognized artist rolls into Modern Arts Midtown with his latest works in tow: John Himmelfarb: Paintings and Sculpture runs from October 2-27, with an opening event on October 5 from 6-8pm.

Even fans familiar with Himmelfarb's art will be pleasantly surprised by new works featured in the exhibition. For about the last nine years, Himmelfarb has centered his work around a new motif: the truck. Also driving his creative impulses is a swing to the three dimensional; small and large scale sculptures are additionally highlighted here.

For those frequent travelers in Omaha's art circles, it's a given that there are merely one or two degrees of separation between participants. That Himmelfarb's orbit came to interweave local collectors, Gallery 72, UNO, and the (then) Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery was predestined.

It began with the friendship that his mother-in-law had established as a college student with Omaha native Kop Ramsey, a connection that continued through their adult years and passed over time and equally by chance through their respective daughters. At the time, the young artist Himmelfarb was expanding his out-of-town patron network by showing his work in other people's homes, and was invited by his friends to bring this experience to Omaha.

After several successful private events in the early 1970s, his hosts introduced him to Bob Rogers, proprietor of Gallery 72, who along with his wife, Roberta, had made it their mission to bring in a variety of national and international contemporary arts to what was then a limited gallery scene. Himmelfarb had his first solo show there in 1979, a heady prelude to his solo debut in New York. He quickly became a favorite and was featured there a dozen times through 2008 before Rogers’ retirement.

He was also introduced early on to Norman Geske, who exercised his affinity for Himmelfarb's ink drawings with an exhibition at Sheldon. He's been an artist in residence at UNO and a visiting artist at Joslyn; public works of art can be seen adorning the exteriors of Conestoga Elementary and the Omaha Public Schools Teacher Administrative Center. It seems fair to conclude that anyone who has not seen his work in the area has not been paying attention.

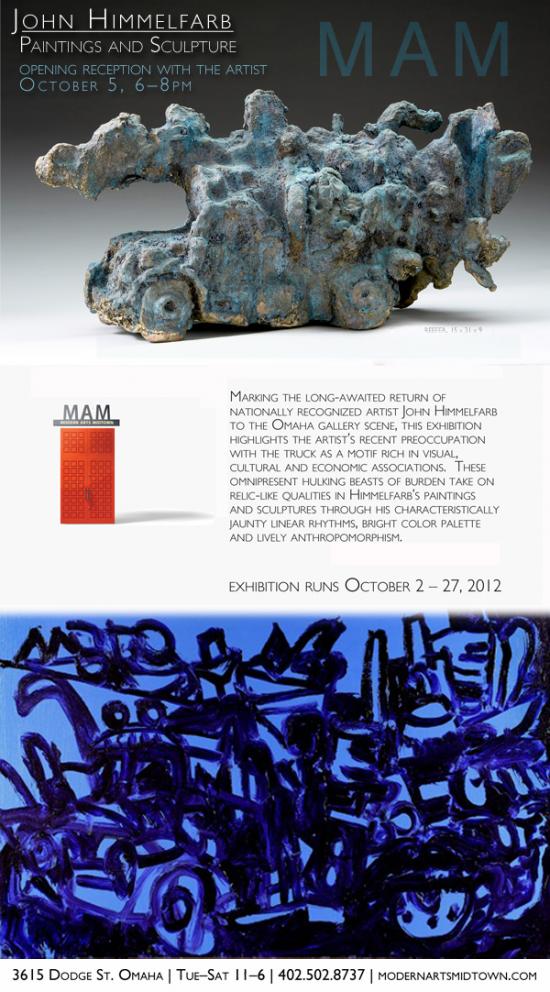

The truck as a motif in the current exhibition is rich in visual, cultural and economic associations. These omnipresent, hulking beasts of burden take on relic-like qualities in Himmelfarb's art through his characteristically jaunty linear rhythms, bright color palette and lively anthropomorphism.

His route to this vehicle was more circuitous, as can be seen in strongly calligraphic drawings such as “Say Some Words.” This elegant ink on paper has columns of ciphers that hint at a legible text of unknown dialect. It is in fact Himmelfarb's invented language of gestures and figures, whose rhythms dance delicately across the page. Such works metamorphosed into more hieroglyphic pieces, including the bronze relief “Wax Eloquent,” in which symbols seem to tell a story; they are Himmelfarb's Rosetta Stone.

For an artist who works along the edge of abstraction and figuration, this is natural, comfortable territory. Why shouldn't a distinct abstract form, perhaps in connection with other such shapes, be capable of communicating ideas, information, emotions and the like in the same way as fully representational art? For example, there's no specific reason that a stop sign must be red and octagonal, but through years of repetition, it is a convention that is understood globally by sight, regardless of any word printed on it. And by inventing and playing with shapes and forms, somehow the truck popped into Himmelfarb's view and became a recurring icon.

He used the opportunity of an artist's residency at the Kohler company, the international maker of bath and kitchen fixtures, to cast a series of trucks in bronze. These craggy, lumpy works seem to describe both the molten nature of their casting and the heavy industrial lugs that they represent. Though reasonably small in scale, they are dense and massive and gloriously imperfect. They bear weighty titles, such as “Fortitude” or “Fidelity,” all assigned after their making and in response to a sense of the human qualities they communicate.

Lighter, even joyous in spirit, are Himmelfarb’s wood sculptures “Blue Motive” and “The Road to Herron.” They are constructions of jigsawed pieces of plywood to which woodcuts or silkscreen prints have been adhered. Almost immediately, they call to mind the wooden toys of childhood and the happiness of play. That they are brightly colored and rendered with an intentionally naive charm makes them even more attractive. And do not miss their big brother, “The Road Ahead Leaves a Trail Behind,” a large orange work in steel, on the plaza outside Modern Arts Midtown.

Himmelfarb's paintings are, in a manner related to the Kohler trucks, more expressionistic and, like his drawings, emphasize the movement of line as well as form. “Dug In” is an energetic exercise in continuous line drawing; deep violet lines of paint fill the blue canvas from edge to edge. The truck is not entirely legible in this tangle of twisted form, but can be recognized by its cab and wheels.

Conversely, “Hero” is felicitous, with its truck chugging across a pink landscape, with a red and blue mass of stuff springing out of its bed in every direction like a bad hair day. Himmelfarb's animated drawing and brushwork accentuate the precarious balance of its cargo. It partakes equally of cartoon animation as it does, say, of early twentieth century Fauve painting.

It's hard to be disconnected from Himmelfarb's work. It contains imagery that is so familiar and speaks about the ways we work, the materials we use (and discard), and the sturdy motion of labor. It looks back, often nostalgically, at grand old machinery, as well as trying to bring the past into the present by revisiting aspects of Modernism to find the life remaining in its approach to picture making. It's a journey Himmelfarb is making; if there's room in the cab, the viewer is welcome to hitch a ride.

The Reader

October 4, 2012