A Tempered View 11.2.12

New oil paintings by Edwin Carter Weitz at Modern Arts Midtown

- by Michael J. Krainak, Freelance Writer in the Visual Arts

You might think after 20 years as a successful graphic artist on behalf of such household brands as Union Pacific, Disney and Pepsi, among others, that any additional métier or passion would represent an alter ego. Not so for oil painter Edwin Carter Weitz of Lincoln, Nebraska whose art has arced beyond that of mere hobby or outlet. In fact, Weitz believes his short six-year “career” in landscape oils has been transformative.

“I am a painter,” he says. “I feel comfortable in that space. Even with everything going on in my life I think I’m supposed to paint. It may be that everything else is a part of my alter ego. And my most authentic nature is as an artist. My graphic arts background is probably an extension of that. Not the other way around.”

It’s an existential argument made by the most committed artists in this area. No matter how an artist “pays the bill,” from college professors such as mixed media artist Tim Guthrie and Wanda Ewing, printing and textiles, to gallery owners Rob Gilmer, photographer, and painter-sculptor Larry Roots, what drives them is their shared search for authenticity.

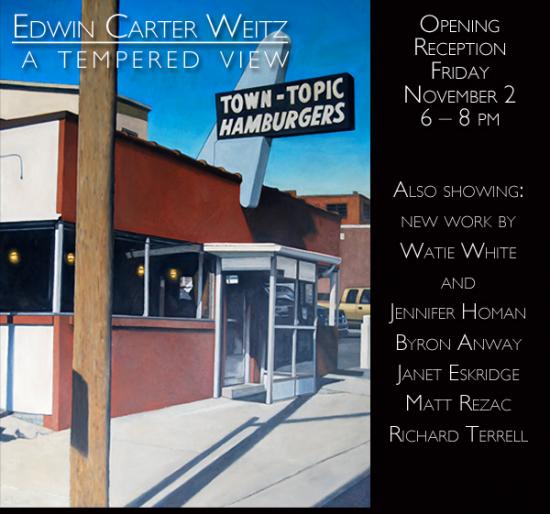

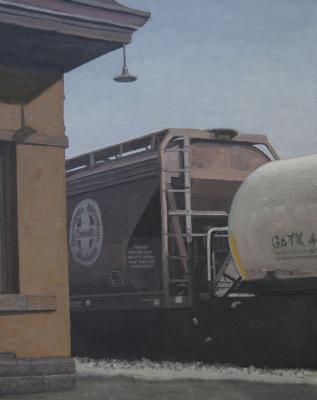

Weitz’s journey is most recently measured with A Tempered View, on display at Modern Arts Midtown during November of 2012. The exhibition is composed of 30 or more oil canvases of varying size that depict mostly cityscapes at once both familiar and remote. His skills in perspective, composition, proportion and line, no doubt enhanced by his graphic arts experience, are clearly evident in all the work here. Yet, it may be his views of small and midtown Nebraska that are the most compelling. For it is these images not only benefit by his craft but are tempered by something more personal that he describes as the “navigation of space.”

“To me, spatial navigation is the result of correct spatial relationships within a painting,” Weitz says. “It happens when the geometry or composition is correct and the eye wants to travel around a canvas. It’s a design thing. Using all the elements of design as part of the total visceral experience. It causes you to move through an environment in ways you normally wouldn’t. Along the way it makes connections, stirs up memories and causes you to feel. That’s why were drawn to it.”

The process begins with a reference image, “always a photo I snap. I fill a wall with the ones I might want to paint. It seems simple, but I make the final selection based on emotion. It has to technically be a good image for sure. But I have to be drawn to the subject. And that’s what I paint from.”

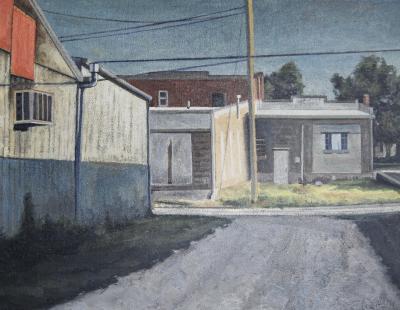

What Weitz is most often drawn to in this show that combines the professional and the personal are the street corners, storefronts, backyards and alleys whose very titles such as “Behind the Scenes in Seward,” “Dumpster” and “Eastside Loading Dock” more than hint at the artist’s desire to connect with a world “far from the madding crowd.” It’s a milieu not of the mundane but of the commonplace and as expressed in his straightforward realistic style it acknowledges the influence of the Ashcan School at the turn of the 20th century and a few artists before and after.

“George Bellows inspires me through his urban landscapes,” Weitz said, “but the two that have had the most impact on me have been William Merritt Chase and Edward Hopper. I consider no painter above Chase. And I relate to Hopper’s work in a deep way.”

That “deep way” might best be expressed by Hopper’s own “Statement” as published in 1953 by the journal “Reality”: “Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist…a vast and varied realm (that) does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form and design. No amount of skilled invention can replace the essential element of imagination.”

What Weitz imagines in his cityscapes is not the Romantic idealism of a Keith Jacobshagen vista but a more objective Realism with its own understated beauty and emotion. Rather than seeking such in nature, partly in deference to his day job, Weitz searches for something special in those locations generally overlooked or taken for granted.

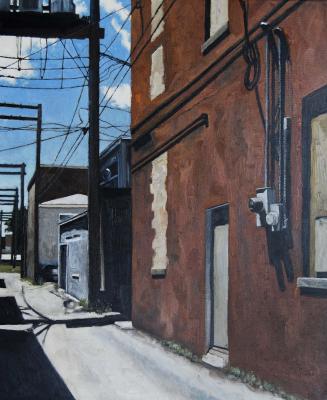

In works such as “Auburn Shadow” and the eloquent “Fog in the Early Afternoon,” Weitz finds not only beauty but solace, moments of peace, in an attempt “to slow down the world.” It’s his public world where everything is based on a deadline or “works at light speed, like in an emergency room filled with instant solutions.” Weitz believes beauty can be found anywhere and as proof that this is more than a cliché he offers the ironic “Blue Sky with Clouds” seen far in the background from the vantage point of a narrow alley and through a maze of telephone poles and wires, a motif in much of his imagery including all three above.

A Tempered View is replete with alleys and vacant roadways generally from a low angle, but the artist can alter one’s point of view. In a previous show Common Ground, Weitz took the viewer in “Omaha” to a downtown rooftop surrounded by the same to enjoy either the solitude of Brando’s Terry Malloy in “On the Waterfront” or that of the Drifter’s anthem “Up on the Roof,” which proclaims “I get away from the hustling crowd and all that rat race noise down in the street.”

In this exhibit Weitz takes the Drifter’s plaintive refrain “I know where you just have to wish and make it so” and magically the “hustling crowds” disappear in image after image. The absence of people in his work as well as the darkened, covered, shuttered and boarded-over windows also suggests that Weitz is exploring a psychological reality as well. It’s a cosmos populated by memories, distortions and now recreations. It’s obvious that locations have a powerful impact on him aesthetically, just as they do the viewer who shares his point of view, but perhaps even stronger is that sixth sense that in this dimension can be revisited and re-imagined again and again.

Another revealing motif that tempers the artist’s vision is his love of signs which could be attributed to his graphic arts background. But a closer examination reveals more. Virtually all signage speaks of community past and present in support of a storefront at the center of what mattered. “Wright’s Corner” not only advertises a town jewelry store but sports a large outdoor clock that everyone keeps time by. “Galaxy Diner,” below a three story apartment building offers “breakfast, lunch and dinner,” most likely for all those living above it. Yet “Town Topic, Kansas City” has more on its menu and mind, a chance to catch up on local news and gossip. But it is “1961,” an iconic image of a town movie theater, in this case, the State, that could pass as a signature piece for the entire exhibit. For below its marquee hangs a poster of what’s currently playing or a coming attraction: “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” This cinematic conflict of illusion and reality mirrors what both movie houses and this exhibit relish in: “the stuff that dreams are made of.”

Weitz enhances the frozen, timeless element of his art by bathing it mostly in the high contrasting light of a mid-afternoon sun. Still, his palette of autumn ochres, oranges and dark greens on a shadowy foreground and blue background cannot be ignored for its own portent. Neither can one’s viewpoint, which is either on the outside of what lingers inside each edifice in his imagery, or is firmly planted at the foot of a long alley or road disappearing into the horizon.

What Weitz is looking at or longing for may best be discovered by following Hopper’s own famous advice; “The whole answer is there on the canvas.” Whatever his art means to the viewer, for Weitz then it must be self-evident. He doesn’t separate his art in any form from himself. He is still branding.

“I think it is,” he admits. “Seems like our work is one of those things that defines us. We all have an identity. A brand. It’s true that this subject matter, matters to me. I think of painting as a never ending journey of discovery….It’s very intimate. Timeless. Spiritual in a sense.”